Attar A, Mirhosseini SA, Borazjani R, et al. Design and rationale for a randomized, open-label, parallel clinical trial evaluating major adverse cardiovascular events (pharmacological treatment versus diet control) in patients with high-normal blood pressure: the PRINT-TAHA9 trial. Trials. 2024;25:563.

The definition of hypertension has become a subject of significant debate, with guidelines shifting the goalposts depending on the governing body. While the AHA defines hypertension at 130/80 mmHg, European guidelines maintain the threshold at 140/90 mmHg. The PRINT-TAHA9 trial protocol enters this gray zone to determine if we should treat “high-normal” blood pressure (systolic 130–140 mmHg) to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). While the intent to clarify treatment thresholds is valid, the study design introduces a confounding variable that may obscure the true driver of any potential benefit: the specific pharmacological properties of the drugs chosen.

The definition of hypertension has become a subject of significant debate, with guidelines shifting the goalposts depending on the governing body. While the AHA defines hypertension at 130/80 mmHg, European guidelines maintain the threshold at 140/90 mmHg. The PRINT-TAHA9 trial protocol enters this gray zone to determine if we should treat “high-normal” blood pressure (systolic 130–140 mmHg) to prevent major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). While the intent to clarify treatment thresholds is valid, the study design introduces a confounding variable that may obscure the true driver of any potential benefit: the specific pharmacological properties of the drugs chosen.

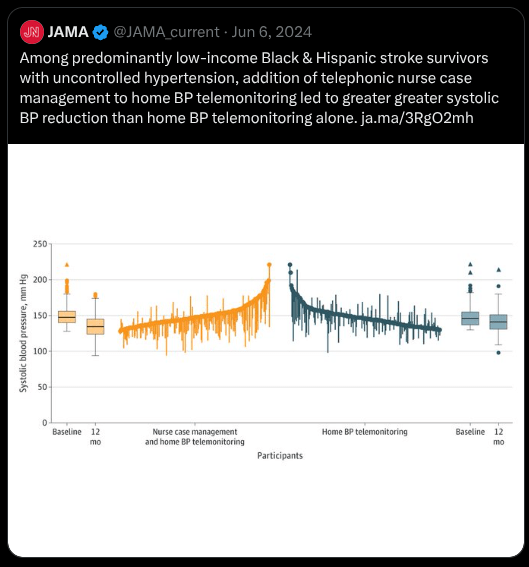

The protocol involves enrolling 1,620 adults with a systolic pressure of 130–140 mmHg and an ASCVD risk score exceeding 7.5%. The investigators are excluding patients with diabetes or prior cardiovascular events to isolate the effect of the intervention. Participants are randomized to either an “intensive” arm receiving pharmacotherapy plus a low-salt/low-fat diet, or a control arm receiving only the diet. The goal in the treatment group is to maintain systolic pressure below 130 mmHg, while the control group receives medication only if their pressure exceeds 140/90 mmHg.

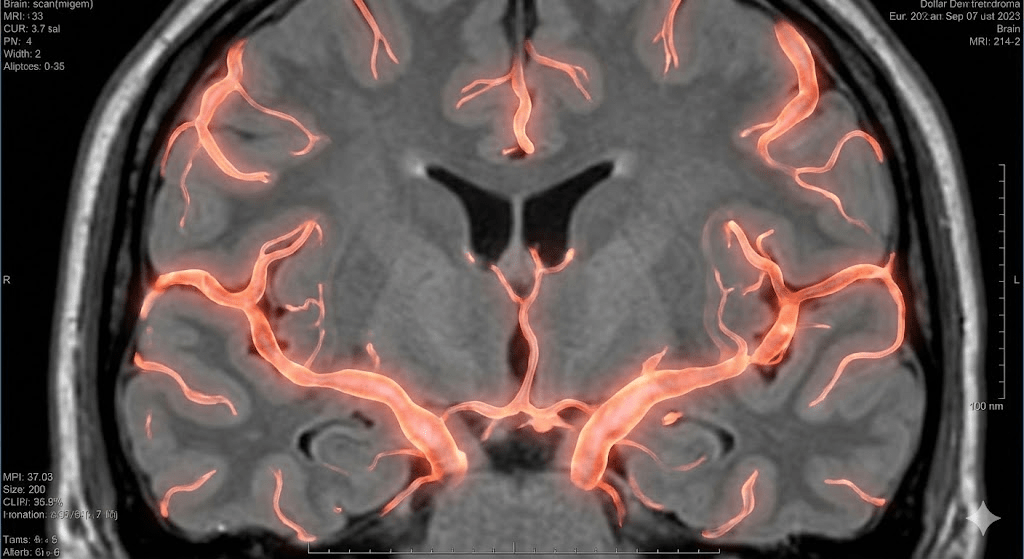

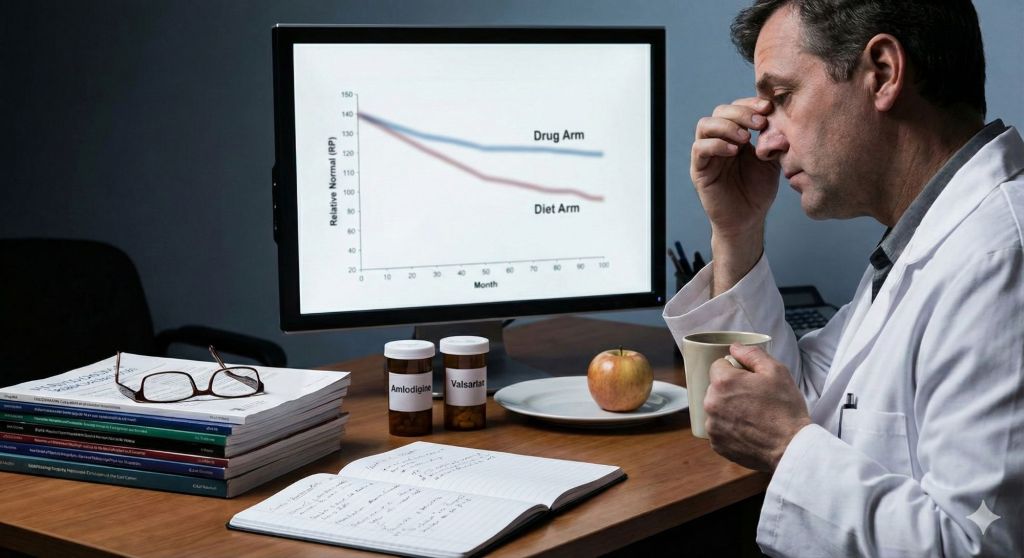

The primary methodological concern lies in the intervention itself. The treatment arm initiates therapy with a single-pill combination of amlodipine and valsartan. This design essentially compares a group receiving dual-agent therapy (calcium channel blockade and angiotensin receptor blockade) against a group managed with lifestyle modifications alone. If the treatment group demonstrates a reduction in MACE, the authors will likely attribute this to the lower blood pressure target. However, it is difficult to disentangle the hemodynamic benefit of lowering pressure from the pleiotropic effects of the drugs themselves.

Valsartan acts on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, which is known to influence endothelial function and vascular inflammation, while amlodipine provides direct vasodilatory and anti-anginal effects. By design, the intervention group receives cardioprotective agents with distinct biological mechanisms. The control group is denied these agents until they cross the threshold of 140/90 mmHg. To truly test the efficacy of the target (130 mmHg vs. 140 mmHg), both groups should ideally receive pharmacological therapy titrated to different goals, although even then the more intensively treated patients benefit from more RAAS blockade. Comparing pharmacotherapy to diet creates a difficult biological comparison.

Furthermore, the open-label nature of the trial introduces the potential for bias. Participants are aware of their treatment assignment, which may influence subjective reporting of endpoints. The primary endpoint includes hospitalization for cardiovascular causes such as angina pectoris. A patient on active medication may feel protected and less likely to seek hospital care for mild symptoms, whereas a patient in the diet-only arm might be more reactive. Without blinding, subjective components of MACE can become noisy data.

Finally, the strict exclusion criteria—removing patients with prior use of statins or antiplatelet agents—aim to reduce confounding, but they also reduce real-world applicability. In clinical practice, a patient with a >7.5% ASCVD risk and elevated blood pressure would likely be considered for lipid-lowering therapy. By stripping away concurrent risk modification, the study creates a clinical scenario that arguably does not exist in standard practice. When the results are published, we must be careful to discern whether we are seeing the benefits of a lower number on the manometer, or simply the benefits of treating vascular risk patients with cardioprotective medication.